There is some prerequisite reading for this post, if you haven’t already read Bipolar, you should do that first.

In the heat of a moment, it is easy to forget or even completely miss important details, and sometimes the things that we do remember seem so pointless in relation to the broader story. It has been exactly a month since I found myself in the back of a pickup truck with 4 other people hurtling down the road towards a Haitian hospital. The little boy who lay on his back between us wasn’t breathing well on his own, and each pump of the bag ventilator was critical to keeping his oxygen levels up and giving him a chance to survive the trip to Bernard Mevs in Port-au-Prince.

I remember pausing at the water cooler before the truck left, and struggling with myself to calm down. I remember the elation I felt when Webert arrived just as Denzly was placed in the back of the truck. I remember taking my watch off and offering it to the medical team as if I was buying a place in the truck with it. I remember the brief discussion at the hospital about whether we should put down the tailgate or just lift Denzly over the side. I remember how I felt when I learned that the rest of the team had skipped dinner, waiting until we returned to eat.

Each person at Tytoo that day probably has their own memories of those hours of uncertainty. Some of those memories will seem so random that they only have meaning for the person remembering it. Some of the moments will gradually be lost to the haze of time, while others will remain sharp and clear for years. As I reflect on that day, it is easy to see the small details of my role, but in focusing on those details, I find that I am prone to missing the larger story.

In my foolishness and the immaturity of my knowledge, I presented the events of that day as starting with a truck pulling into Tytoo. I know better now, and I would like to tell you the rest of the story, including the news I received just this Saturday.

Allie has been in Haiti for roughly 2 years, and in some ways, she is where this story starts. When we arrived in Haiti we shared our ride to Tytoo with Denzly, who we picked up at the hospital. Allie had been approached by one of the boys relatives and was shown a picture of Denzlys crazy rash, because of her role at Tytoo, Allie has developed a reputation for being someone you go to when you need help. Allie had arranged for Hillary to take the boy and his mother to the hospital for some tests. Hillary is a Canadian paramedic, and is the coordinator for medical teams who visit Tytoo. She had arrived in Haiti just a few days before us, and would be leaving with us at the end of our trip.

On Thursday we went to Denzly’s home, hoping to try some anti-fungal medicine on his rash since the antibiotics he had been taking hadn’t yielded any obvious results. We pulled up in front of his home to find that he had been taken to a “church service” by his mother, who hoped he would be healed spiritually. We piled back into the truck, and went back to Tytoo, hoping to try again the next evening. In light of what happened the next day, it really felt like a missed opportunity.

When the fateful Friday night arrived, Hillary was already at Bernard Mevs with Annalisa, a child at Tytoo Gardens who has brittle bone disease. On Friday morning, I had watched as Hillary loaded Annalisa into the Kia, a mid sized white truck owned by Tytoo. She had broken her femur while turning over in bed during the night. In fact, Annalisa would stay at the hospital all day waiting for a cast that was promised in two hours, but would never be applied. She would have to return on Saturday for her bright blue cast.

Hillary was with Annalisa all day while they waited at the hospital, meaning that when Denzly arrived at our gate that evening, the person most experienced with transporting a child in distress was not with us. Since they had taken the Kia to Port-au-Prince, when Denzly arrived, we didn’t have a fast and safe vehicle to take him to the hospital. It would be at least 45 minutes before the truck could get back to Tytoo, far too long to wait.

Further compounding the situation was the fact that Kori, Jen, and Troy hadn’t had any time in the small onsite clinic. They hadn’t been able to familiarize themselves with the equipment, or where it could be found. This lead to some frantic searching as they looked for equipment they weren’t even sure the clinic had. The nearest ambulance was without a driver, and the nearest hospital wasn’t going to be able to handle a child in Denzly’s condition.

It was as if our hands had been tied by threads of unexpected circumstance. Each strand entangling us to paralyze our efforts.

It was only during the week that followed that Friday night that I learned the full scope of what had happened.

In our debriefing time one evening, I remarked to the group that I wouldn’t have even been in

the truck if Hillary had been with us instead of at the hospital that day. There was barely room for me as it was, and with a 4th medical person in the back of the truck, I would have had nowhere to cling as we sped down the road. While I hadn’t served a valuable purpose in the truck, I knew that this story would be powerful, and I remarked that I was glad it had worked out for me to go along. Hillary agreed, but then continued the story.

She proceeded to say that if she hadn’t been at the hospital all day, they may not have even let Denzly in! She said that when a Haitian hospital is presented with something they are unfamiliar with, aren’t sure they can help with, or even if they are just too busy, they may turn you away at the gate, forcing you to look elsewhere. When we arrived, there were already 2 gunshot wounds in the E.R. and no one was available to begin care right away. Hillary quietly finished by saying that if she hadn’t been there, we probably would have been turned away.

Before we left for the hospital that night, I ran back to the room to grab every penny I had with me. I wanted to be prepared to pay for whatever needed paid for to ensure Denzly could be seen by the hospital. By North American standards, I didn’t have much with me, and I knew that I needed to pay my extra baggage fees on the way home, but weighed against a life, I knew which choice I would be compelled to make if the moment came. It would cripple me financially until the end of the trip, but what choice would I have?

One of the people in the front of the truck that night was Kayla, her husband Webert was the driver, and the truck belonged to them. Kayla works with Touch of Hope Haiti, and in the last year she had done a lot of fundraising so she could set up what she called “The Lazarus Fund”. When Hillary came out of the door and started talking through the details of paying for Denzly’s care, I was standing next to Kayla. It quickly became apparent that even if I gave everything I had, it wouldn’t be enough. As I was still working up the courage to mention the stash of cash I had brought, without batting an eye Kayla that they would take care of it. She said that the reason this fund existed was for exactly this sort of situation, and that she was so glad that she had been able to raise enough to take care of this boy without thinking twice. Would Kayla have been with us if the Kia had been at Tytoo when Denzly arrived?

As I put aside my own memories of the event, I start to see the larger story unfolding.

The threads of circumstance that seemed to bind us, were perfectly placed to free us.

From a broken leg and a long hospital wait, to open seats and visiting medical teams, each moment of the weeks leading up to that moment on Friday night was completely outside of the ability of any one human to control. It was as if each unexpected circumstance was a thread on an unseen loom, skillfully woven together with a precision unmatched by human hands. Each moment a seemingly insignificant strand, easily snapped, but together forming a picture that no one could have expected. It is in this larger picture that I find myself able to say this.

It is good to be used by God.

Each moment was ordained by God. I didn’t see it right away, but the more I reflect on that night, the more clear it becomes to me. I could say that we were remarkably lucky, but that would be denying God’s presence in each moment. God was able to use us to do his will because he was able to place us where we were needed. Our role in the events takes a backseat to the elaborate weaving done by God to ensure all would go according to his plan.

In fact, God continues to weave these threads even now.

The “church service” Denzly was taken to on Thursday night was most likely a voodoo ceremony intended to heal Denzly. What we originally believed to have been a rash, we now believe may have actually been a chemical burn caused by a voodoo “curse”. When Denzly’s mother removed him from the hospital against medical advice, she neglected the provided medicine in favor of voodoo “tea”. Her anger at us for interfering with the care provided by the witch doctor was palpable. As we neared the end of my time in Haiti, we almost felt defeated by the situation.

Before I left, Allie and I stopped at Denzly’s home to check on him. I didn’t expect a warm welcome, but Allie was determined to see him. As we walked up to the house, we could see Denzly standing outside, a frozen juice pouch in hand. He didn’t acknowledge us as red juice dripped from his deformed lips to the dirt beneath his feet. I shudder to say it, but he was truly like a zombie, it was as if he wasn’t actually there. His family gathered around and began talking with Allie as I began to fear that while we had saved his body, the lack of oxygen had left his mind impaired, unable to rejoin the world he had left behind.

Allie managed to cut through the dark clouds that had formed in my brain as she said that his heart was beating really fast. She kept feeling his stomach and his chest, while I looked stupidly at her and asked her to count the beats. After a few more moments of discussion she asked me to feel his heart beat. I hesitated, not knowing what I could do, but eventually I reached out my hand to feel his heartbeat.

It was too fast to count.

When Allie told the mother to take Denzly to Tytoo’s clinic yet again, I expected resistance. Instead, the mother quickly agreed. Once at Tytoo they made arrangements with the mother to return to the hospital, and this time to stay until Denzly was better. She accepted the conditions and Denzly returned to the hospital. I don’t know that I expected Denzly to survive. I could only hope that God had chosen to weave together this story so that Denzly and his family could know the healing power of Christ over voodoo.

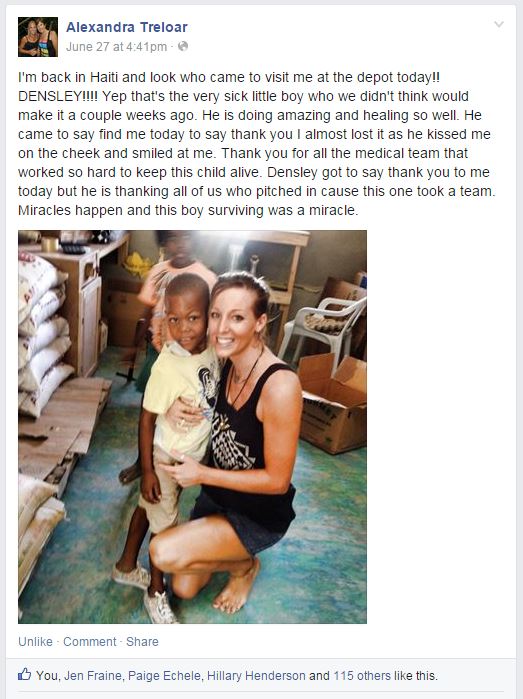

I left the next morning, and Allie left the day after. It would be nearly 2 weeks before I would learn what happened to Denzly.

In all our time with Denzly, I had never seen him smile.

If you are interested in donating to The Lazarus Fund, please contact Kayla by going to her website. She will be able to tell you the most pressing needs, and how to donate if you are interested.